Drought + Heat = Increased Impacts

Dry conditions in the area of Lake Mendocino in Mendocino County following two critically dry years. Photo taken April 20, 2021

***This is part 5 in a series of articles DWR is publishing about California’s 2021 water year and dry conditions.

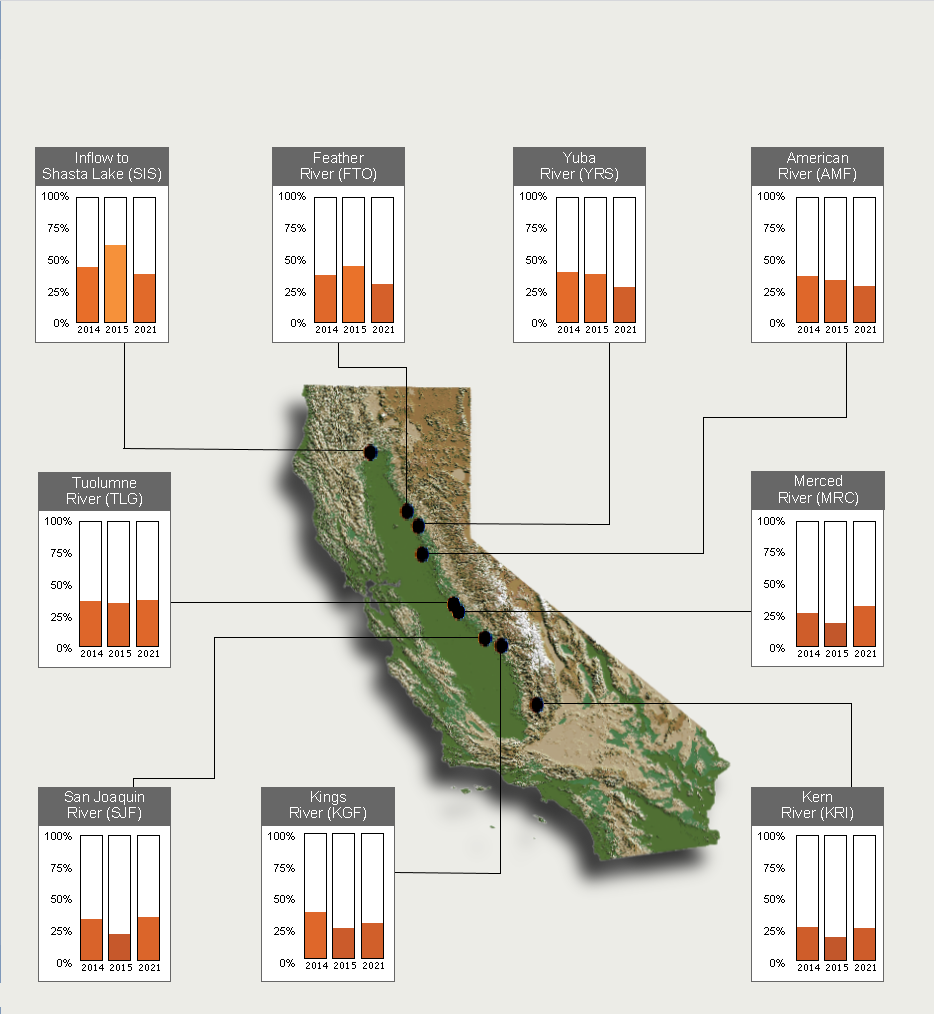

As we approach the official start to summer, California and much of the Southwest are experiencing a heatwave that will set new temperature records in some areas. Warm temperatures are affecting drought impacts. Runoff this year in key mountain watersheds remains on a par with that of 2014 and 2015, the two warmest and driest years of California’s last drought, despite this year’s statewide April 1 snowpack being at 59% of average as compared to 25% of average in 2014 and 5% of average in 2015. The decrease in runoff efficiency (the runoff that occurs in response to a given quantity of precipitation) is a troubling, yet expected, outcome of a warming climate.

Outcomes of this shift in conditions were seen earlier in the spring when forecasted Sierra Nevada and Cascades runoff failed to materialize, triggering the May 10 expansion of the Governor’s drought emergency proclamation to cover Central Valley watersheds in response to needs for water rights administration actions to preserve reservoir storage. Estimated statewide reservoir storage at the end of May was 67% of average.

Changing hydroclimate conditions have implications beyond decreased water supplies. New runoff forecasting technologies must be developed to replace old methods that relied on simple linear regression techniques based on historical data that is no longer reflective of present conditions. Increased wildfire risk is occurring, as demonstrated by the number of records set in recent years for damage costs and number of acres burned. Wildfire damage to water infrastructure is increasing, with catastrophic damage occurring at municipal distribution systems such as those in Santa Rosa and Paradise. In recent years, wildfires have forced precautionary evacuations of personnel at the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation’s Keswick Powerplant and DWR’s Hyatt Powerplant.

Water Year 2020 was California’s 13th driest based on statewide precipitation and 5th driest based on statewide runoff. It is likely that the present water year will end up being drier, possibly coming in at second driest for runoff (behind 1977) for some parts of the state. Present very dry and warm conditions increase the risk of a dry 2022 because of moisture deficit in the hydrologic system, including depleted soil moisture. Above-average precipitation would be needed to achieve average runoff.

The Colorado River Basin, an important water source for Southern California, has also been experiencing prolonged warm and dry conditions, resulting in storage in both Lake Mead and Lake Powell having fallen to about 35% of capacity with a first-ever Lower Basin shortage forecasted for 2022. Although California’s allocation of Colorado River water would not be cut based on the projected Lake Mead elevation, the shortage declaration is a warning of future water supply risk to an historically highly reliable source.

Although we’re just approaching the first official day of summer, we should be planning ahead for responding to impacts of continued dry conditions in the coming winter.

Full natural flow at DWR forecast points on selected California rivers shown as a percent of average to date. Data as of midnight June 16, 2021